Consolidated Financial Statements in the Public Sector: International and National experience. Edition №3

This Q&A rubric provides a structured overview of the principles and steps involved in consolidating the financial statements of a country’s entire public sector. It outlines the key considerations and processes essential for achieving accurate and transparent reporting in governmental financial consolidation.

Q1: What are the principles of consolidating the financial statements of a country’s entire public sector?

A: The principles of consolidating the financial statements of a country’s entire public sector are the same as those pertaining to privately-owned corporations. However, the business of government is far more complicated than for companies and this leads to difficulties in the practical implementation of ‘whole-of-government’ financial consolidation. The difficulties include: scale; span of control; bureaucratic mindset; and managing different standards. Aligning the scope of the consolidated public sector financial statements with the institutional structures according to standard classification models such as ESA 2010 is a good basis for reporting the activities of government;

Consolidation should be based on what a government controls. For that you need to record transactions on a ‘from-whom-to-whom’ basis. Local government should be incorporated in a country’s consolidated public sector financial statements. However, local government entities may produce accounts according to their own accounting policies or delay their reporting to the centre.

The international standard for social security pensions accounting is to exclude them from the balance sheet. Only the (mostly non-current) liabilities of public sector employee pensions are included in a government’s financial statements.

Few countries report actual consolidated financial performance of the whole government and even fewer against the relevant budget forecasts.

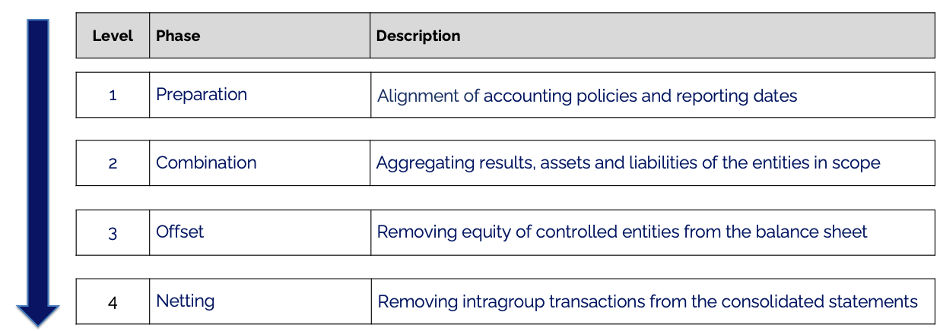

Q2: What are the steps to consolidation?

A:

Q3: What are the differences in government financial reporting between Ukraine and the UK?

A:

In Ukraine:

- Emphasizes state and local budget execution statements on a cash basis

- The Ministry of Finance is required to produce a detailed annual budget execution report of the consolidated budget within three months of the end of the fiscal year

- Not compelled by law to publish a full set of consolidated financial statements encompassing all its activities at all levels

In the UK:

- National Accounts based on ESA 2010 report a government-wide measure called Public Sector Net Debt (liquid financial assets including cash, less financial liabilities) – modified cash

- The Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 forces the government to publish a set of accounts for all entities funded from public money

- Preparation of consolidated financial statements for the UK public sector in line with adapted IFRS is mandated by law

Q4: How do National Accounts differ from Whole of Government Accounts (WoGA) prepared under International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS)?

A:

| Area of accounting | National Accounts | WoGA |

| PPE | Assets are recognised at cost less depreciation and are not revalued. Only impairments caused by obsolescence or accidental damage are recognised | Assets are revalued periodically and assessed annually for impairment compared to their carrying value |

| Depreciation of PPE | Is calculated using standard statistical models, high level data and asset life assumptions | Is calculated for each asset individually based on its estimated useful economic life and residual value |

| Public Sector Pensions | Recognises expenditure as it is paid. The future liability for pensions is not recognized. Pension entitlements are not netted against expected revenue or expected household social contributions | State pension expenditure is recognised in the period of entitlement. A liability is shown only for government employee pensions. Pension assets are recognised when contributions are made to the pension fund |

| Provisions | Recognises provisions only when there are actual payments). Amounts expected to be paid out in future because of past events are not recognised. | Recognises expenditure when it becomes probable that a payment will be needed because of past events. |

Q5: How does the non-consolidated nature of National Accounts, as per the ESA 2010, impact the compilation of financial data, especially in differentiating government and other institutional units’ liabilities and in calculating ratios of revenue or expenditure to GDP?

A: As a rule, the accounting entries in the ESA 2010 are not consolidated, as a consolidated financial account requires information on the counterpart grouping of institutional units. This requires financial transaction data on a from-whom-to-whom basis.

For example, the compilation of consolidated general government liabilities requires a distinction to be made among the holders of government debt between government and other institutional units

For calculating ratios of revenue or expenditure to GDP it is considered better to eliminate the internal churning of funds and include only those transactions that cross the boundaries with non-government sectors.

Q6: What are the contrasting definitions of consolidation in financial reporting as per the National Accounts (ESA 2010) and the National Standard of Accounting in Ukraine, and how do they differ in the process of preparing consolidated financial statements?

A:

National Accounts (ESA 2010):

Consolidation in the financial account (revenue less expenses) refers to the process of offsetting transactions in financial assets for a given group of institutional units against the counterpart transactions in liabilities for the same group of institutional units.

National Standard of Accounting (Ukraine):

- Consolidated financial statements shall be prepared by orderly addition of indicators of controlled and controlling entities;

- Balances and transactions between entities of the same group are mutually excluded, including income and expenses;

- Consolidated financial statements shall incorporate financial statements as of the same reporting date;

- Where possible, the financial statements of all entities are based on a single accounting policy.

Q7: What defines the consolidation boundary?

A: The public sector entities within the boundary for consolidation are:

The general government sector consisting of:

- Central government

- Statutory entities funded by government and providing services

- Local government

- Social security and other budget funds

- Non-commercial public corporations, plus

- Commercial public corporations i.e. public sector units under the control of the government that engage in ‘market output’ (ESA 2010).

IPSAS uses the same unit definitions for the public sector (general government sector including non-commercial public corporations + commercial public corporations).

Q8: How is control over the consolidated entities defined for the whole of government consolidation?

A: Defining the whole of the government consolidation boundary involves establishing control between the public and private sectors.

ESA 2010 introduced guidance on delineating the two, focusing on whether the government exercises significant control over the general corporate policy of the unit.

Factors determining control include the power to appoint or remove board directors, influence over senior management appointments, shareholder voting power, contractual positions, and control over financing arrangements.

Q9: What does the Whole of Government Accounts (WoGA) in the UK consolidate, and what are its key features?

A: The WoGA in the UK consolidates various entities and provides a comprehensive view of the government’s financial position.

- Consolidates 5,500 entities from central government, local government, extra-budgetary units and social security funds (pensions, welfare, unemployment);

- Provides a complete picture of the government’s financial position including future obligations (e.g. government debt, pensions and PPP contracts);

- Independently audited giving both Parliament and the outside world greater confidence in the figures;

- No one body has the ability to control all of the bodies within the consolidation, therefore no ‘parent’ entity is shown in the financial statements;

- The consolidation boundary is determined by UK government definitions of public sector bodies rather than the concept of ‘control’;

- The WoGA document for 2020-21 runs to 278 pages and contains financial statements in accordance with adapted IFRS plus notes, over 233 pages.

Q10: What are the difficulties with consolidation?

A: It is only possible to provide a full picture of the resources and risks for the public sector if there is full consolidation, including general government bodies and public corporations at ‘whole of government’ level. According to the ACCA, only 5 countries (UK, Australia, New Zealand, France and Sweden) are known to consistently produce whole of government i.e. fully consolidated public sector accounts.

The preparers of the UK’s WoGA 2020-21 stated that 21 bodies out of 5,500 did not submit data for consolidation. “This was not significant to WoGA as a whole.”

The public sector auditor qualified the same 2020-21 financial statements citing the incomplete boundary used for the preparation of the consolidation, inconsistent accounting policies and the different year-ends of some group entities among the factors leading to audit qualification.

The public sector auditor stated that for WoGA 2020-21 that some material bodies (e.g. a large bailed-out bank taken from the private sector after the financial crisis of 2009) should have been included in the accounting boundary and would have been if the accounts had been fully prepared with reference to the IFRS concept of control.

The independent academies did not follow IFRS 10 in respect of coterminous year ends. The preparers of those financial statements did not provide enough information about the period from their year-end to the end of the year for the WoGA as a whole.

Qualification of the 2020-21 accounts was also necessary because the local government sector did not apply the same accounting policies as the rest of government. For example, valuing assets at historical cost rather than depreciated replacement cost. The difference (undervaluation) was estimated by the auditor to be almost 7% of the value of the assets in the 2021 WoGA balance sheet.

Q11: How are state social security schemes treated?

A: Being part of the obligations of government to administer social welfare schemes, payments under social insurance, social assistance and social transfers are naturally consolidated in the whole of government financial statements. Regarding state pensions for all citizens: this could be an enormous liability for the government if the relevant accounting standards forced it to recognise all the amounts to be paid to pensioners in future.

IPSAS 42 (Social Benefits) dictates that the government recognises its liability for state pensions when the eligibility criteria are met. For example, an individual needs to be i) retired and ii) alive at the beginning of the next month to receive that next benefit payment, thus satisfying the eligibility criteria in each instance. Only that liability for the next month needs to be recognised.

If the state pension is paid in full during the month, then the balance of the state pension liability is nil.

Therefore, it is likely that any unpaid state pensions will be classified as short-term liabilities. These known amounts accounted for as short-term liabilities will not need to be discounted to present value (IPSAS 42, IAS 26).

All payments in the year of state pensions is shown in the line ‘Social Security Benefits’ in the Statement of Revenue and Expenditure (£258 billion in 2020/21).

It is a significant decision to interpret the liability for social security pensions as set out in IFRS/IPSAS as being excludable from the financial statements. It is widely reported that the net liability for state pensions in the UK sits in the region of £4 trillion (2022), about the same amount as all the recognised debt in the balance sheet. The pension liabilities shown in the WoGA balance sheet relate to the consolidation of employment pension schemes for civil servants in central government, public service workers in health, education and other services and local government officers.

Q12: What is involved in the consolidation of the UK local government entities, and what challenges are associated with it?

A: To be treated as separate units for consolidation, local government entities must be entitled to own assets, raise funds, and incur liabilities by borrowing on their own account. They must also have discretion over how such funds are spent, and they should be able to appoint their own officers independently of external control;

IFRS 8 is interpreted for WoGA to mean that the government will report separately information about each operating segment (central government, local government and public corporations).

IFRS 10 is adapted for WoGA to eliminate in full non-domestic business rates payable by consolidated entities to local authorities.

WoGA shall also consolidate (local) Council Tax and business rates revenues recognised in local authority collection funds.

The 2020/21 WoGA states in the introductory ‘Performance Report’ (paragraph 1.12) “all UK central government departments submitted consolidation data for 2020-21, but a significant number of English local government bodies did not. Ordinarily, the data would show a grant expense in central government, with a matching amount of grant income reported by local government bodies and then expenditure as the grant is used for its intended purpose. For the bodies that didn’t submit data in 2020-21 this chain is broken, and WoGA will show only the grant expenditure distributed to those bodies by the central government.”